Do you hate yourself?

Maybe you're a Millennial Woman who grew up in the toxic milieu of the early 2000s

The Next Pleasure Shelf Book Club:

The Books That Shaped Me With Singer, Paris Paloma | October 11th @ The Nest, Treehouse | 10am -12pm

There are only a few tickets left so grab yours here. Tickets are just £10 for paid subscribers (the ticket code is below the paywall below).

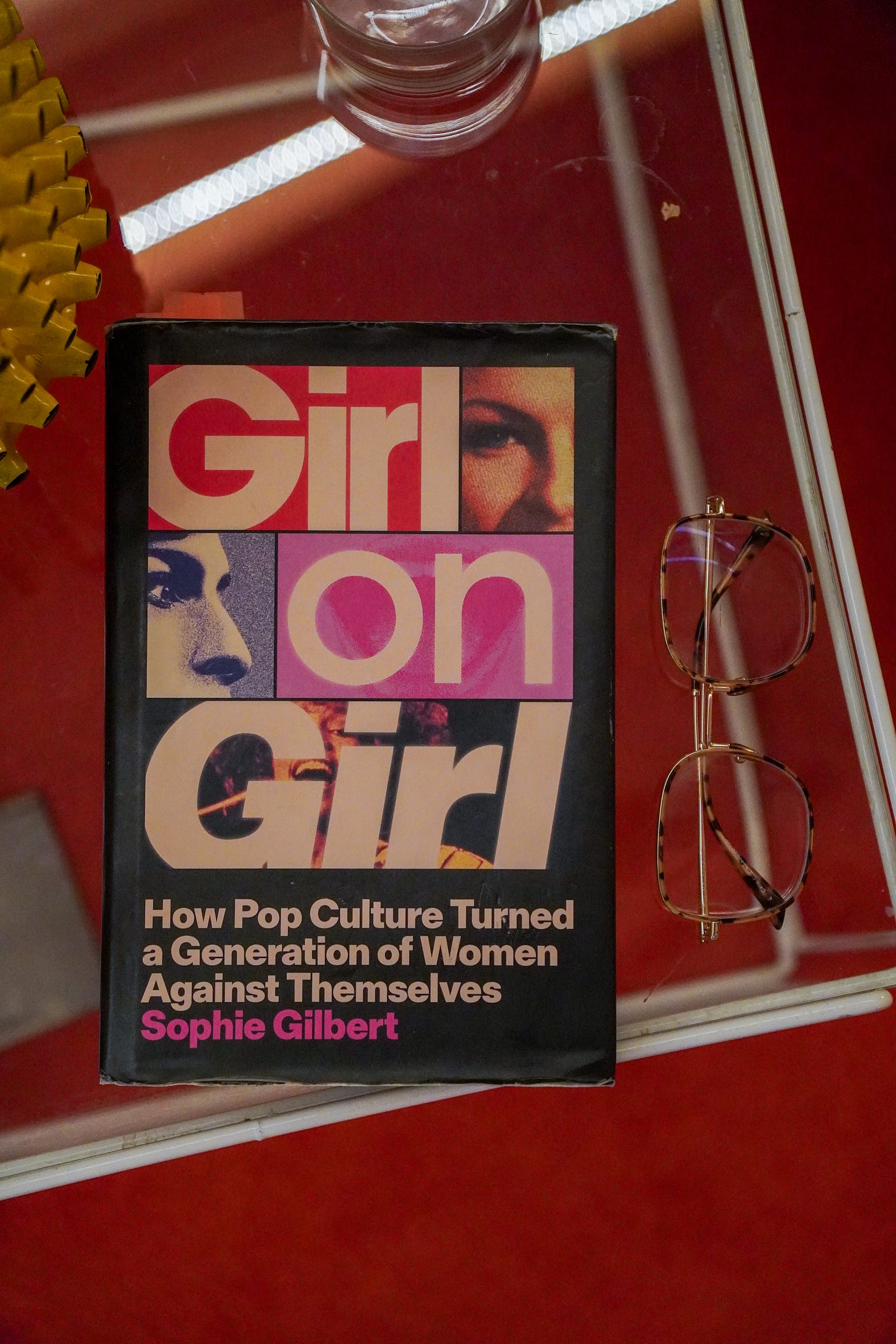

September’s book club pick was Girl on Girl by Sophie Gilbert, a brilliant book exploring how late 90s/ early 2000s pop culture turned a generation of women against themselves and each other.

I sat down with Sophie last week for the second instalment of The Pleasure Shelf book club to dig deep into what she discovered in over a year and a half immersed in researching early naughties pop culture.

It may come as little surprise to my fellow millennials that this was an era steeped in casual misogyny, overt sexism and a deeply problematic sexual politics that Sophie says has left a troubling imprint on feminism and womanhood today.

“The message was simple: your body is a project, and it’s your job to keep renovating.”

Read our conversation below. (Paid subscribers will get access to the full conversation below the paywall + the full event recording over the weekend).

*The original conversation has been edited down for clarity and brevity.

How 90s/2000s pop culture fucked us with Sophie Gilbert

ELB: Let’s start at the very beginning of your journey with this book. Why this book, and why now? What was happening in your life and in the culture that pushed you to turn back to the 90s/early-00s and interrogate what that era did to us?

SG: A few currents converged. I had twins during COVID in New York. That newborn period is a full self-dissolution: no sleep, no reading, no films — nothing that had always structured my identity. It made me realize how thoroughly culture had built my sense of self. Then Roe v. Wade was overturned. Even back in London, I felt enraged and newly powerless — I’d assumed progress went one way only. Brilliant people were parsing the politics, but I kept thinking: what did culture do to us? As an older millennial I wanted to revisit the 2000s, a period of extreme cruelty and dehumanization of women in media, to frame it, to ask what it did to me and to the women who lived through it, and how it links to now.

ELB: You’ve said that stepping out of culture (postpartum) let you see it more clearly. When you returned to work, what were the specific signs that popular culture had shaped you — your body image, your thinking, your taste — often against you?

SG: My first pieces back all orbited identity and manipulation. I reviewed Physical (Apple TV+) and it became a personal essay about postpartum body alienation and the cultural scripts that teach women to loathe our bodies. I was noticing the same themes everywhere — how culture instructs us to feel, desire, and self-police — and with less time (hello twins) I only wanted to write pieces that counted.

ELB: This is such a thorough yet precise book. What did the research actually look like day-to-day? Were you in archives, chasing down ephemera, mainlining reality TV and, yes, porn?

SG: It’s my Atlantic process scaled ×50. I read everything: academic work, criticism, biographies, tabloid detritus, even Daily Mail pieces — you can find telling fragments anywhere. I lift quotes, make huge notes, then hunt for a through-line. My master Google Doc hit ~200 pages and started crashing, so I broke it into chapters. I also cheat and begin with an imagined headline — it forces clarity about what I’m actually arguing.

ELB: The title Girl on Girl, at first intended as a joke, came to feel deeply appropriate as your research went on. Can you tell us about that shift?

SG: The phrase captured two linked harms: culture teaching women to hate themselves, and to be suspicious of other women, a breaking of sisterhood replaced by an individualist “girl-boss” ethos. I didn’t plan for porn to be so central, but the deeper I went the more it underwrote shifts in power, aesthetics, and behavior from the 70s onward — sometimes negatively, sometimes in productive ways.

ELB: You consciously resist memoir. Editors nudged you to add more of “you,” but you hold the book as history. Why keep yourself mostly out, especially when women writers are often steered toward confessional writing?

SG: It wasn’t a choice so much as it was a failure. I have written about myself in the past. I’m not afraid of doing it. I love reading personal writing. I feel like women who are able to be completely fearless on the page do a service for all of us, because they write down just these ways of being that otherwise we might never be in touch with. But every time I kept writing myself into the text it just was so bad: it was cringy, or it wasn’t getting at the point.

In the end I felt strongly that this was a history book. Women’s cultural history is rarely treated as capital-H History but I wanted to give it that weight. Small personal moments remain, but they’re not the point.

ELB: Let’s talk beauty and the body: the 90s/00s didn’t invent the beauty myth, but they re-engineered it. How did reality TV and the early internet narrow the ideal and normalize transformation as obligation?

SG: Reality TV shifted fame from talent to visibility. If you opened up your life, and crucially your body, to the cameras, you could be rewarded. The ideal was extremely narrow: thin, white, often blonde, hyper-groomed, the Paris-Hilton silhouette turned from aspiration into expectation. Around it grew a full “makeover logic,” where improvement was never-ending and public: there were only a couple of dozen makeover shows in 2004, and by the end of the decade there were more than 250. The message was simple: your body is a project, and it’s your job to keep renovating.

The Swan was the clearest, and bleakest, expression of that logic. The series took women labelled “ugly ducklings,” removed them from their families for weeks, and put them through strict diets, intensive training, and a battery of cosmetic and dental procedures — often 12 to 14 surgeries, scheduled close together. There were no mirrors in the house, so they couldn’t see their changing faces. Each episode built to a reveal on a stage, and at the end of the season contestants competed in a beauty pageant to crown “the Swan.” It wasn’t just transformation; it was transformation as obligation, judged by experts and an audience, and severed from the woman’s everyday life until she could be presented as “finished.”

ELB: You evoke the Terry Richardson moment, where overt boundary-crossing sat at the epicentre of “cool.” Why did that feel normal, even aspirational, then?

SG: In that moment, the worst thing you could be was uncool or a prude. “Cool” meant acting like nothing shocked you, that you could handle sexualisation and not make a fuss. Photographer, Terry Richardson, sat at the centre of that world: the coffee-table books, the endless celebrity shoots, the fashion magazines that conferred legitimacy. He photographed everyone, even Barack Obama, in the same year he bragged in print about how models got cast (“it’s not who you know, it’s who you blow”). That symmetry told you everything about where the power sat.

Because the gatekeepers, the Face, i-D, the big glossies, the brands, kept validating him, the behaviour felt normal, even aspirational. No one wanted to be on his bad side, so women learned to negate their own instincts — to quiet the voice that said, this is off — and perform unbothered. That’s the same logic the pornified culture rewarded: prove you’re cool by tolerating more.

It had that Jimmy Savile quality of “hiding in plain sight,” except here it was wrapped in fashion’s stamp of cool. The validation made the boundary-crossing feel like an aesthetic, not a warning sign. The social cost of refusing was high, so the industry taught us to swallow the alarm.

ELB: The book’s central arc is the pornification of culture. You trace a 90s split after AIDS: a chastity-flavoured “new traditionalism” vs. a voyeuristic celebration of sex (Madonna, Real Sex, fashion’s erotic dominance). Then VHS and the internet make sexual imagery ambient. What changed when porn had to compete in that new attention economy?

SG: SG: Once sexual images were everywhere — first through VHS at home and then online — porn had to differentiate itself. If anyone could get “basic” for free, what would people still pay for? The answer, in practice, was escalation. You can see a clear turn in the late 90s and early 2000s toward content that was harder, louder, more shocking — and often more degrading to women. That shift didn’t stay inside porn; it seeped into mainstream expectations. The “Overton window” of what counted as normal moved, and you feel it in the rise women report of being choked or gagged during sex without having asked for it.

I’m not anti-porn — humans have always made sexual images, in every medium available. What worries me is how a very specific, male-gaze style of online porn ends up training people: it rewards performance over feeling, escalation over communication, and it teaches a script that many then carry into real encounters. When the attention economy prizes extremity, those are the behaviours it amplifies.

*The rest of the interview continues below the paywall below and includes discussion of Bonnie Blue, the commoditisation of terms empowerment, what next for feminism, and more.

Sézane kindly dressed us for the event so I’ve linked our outfits below:

*Affiliate links

Sophie’s lewk:

My lewk:

And thank you to Bed Intentions who sent everyone home with a stash of oil-based lube. Check them out! We love a female-founded sexual wellness biz!